Beau Rhee on mindfulness in consumption and the value of personal encounters

Beau Rhee is limitless. Creating and working as an artist, choreographer and educator, Beau's work is a constant exploration of our rootedness with the Earth, be it through movement in her choreographies to her class on Sustainable Systems, which she teaches at Parsons School of Design.

Beau, tell us a bit about yourself.

I often feel like a sea creature living on land for this lifetime. Earthling titles: choreographer, artist, designer, professor. I was born in New York State, molded by years in Boston, Seoul, New York, Geneva and Paris. Trilingual, tri-cultural, a bit in-between spaces. Gestures make the most sense to me. I am dyslexic and I have synesthesia. I was told by a Korean acupuncture master in college that I would always live near water, and that if I did not pursue the arts I would be unhappy and unfulfilled in my life. Et, voila! I am a Libra (sun & moon, apparently Aquarius rising). Daughter of a biologist-professor dad & writer mom.

What was the stimulus for founding Atelier de Geste? How has it evolved over the years?

The idea for Atelier de Geste (ADG) started when I was in my MFA program in Geneva (at the HEAD or Haute école d’art et de design de Genève) in 2012. I wanted a studio name because it meant that my work had to be greater than myself.

I had always admired the legacy of artists like Eileen Gray or Sonia Delaunay, whose creative practices also fueled/lived alongside businesses – Gray’s Galerie Jean Desert & Sonia Delaunay’s textile business.

As somebody who is approaching everything I am creating from a choreographic point of view, the name Atelier de Geste just kind of stuck solid with me one day. I ran it by one of my mentors in grad school, Christophe Kihm, who enjoyed it because Atelier has the link to workshop and fabrication, which is an interesting pairing with Geste (gesture) which is so ephemeral. Contrast and tension is interesting. Geste is a masculine French noun, so technically it should be Atelier du Geste, but I thought it was fun to be irreverent and changed it to Atelier de Geste.

I worked on developing ADG my last year in grad school, and spent 2013 in brainstorm mode, planting seeds and creating the genetic structure of the studio. The first public Atelier de Geste event was in the Fall of 2013. The first years, 2014 - 2015 were much more focused on the choreographic scent editions and the costume design, and other artist editions that accompanied my performances from graduate school. It was exciting to develop these works to a more refined level and to receive recognition from press like Coolhunting and Elle, and to be relevant in the style and design space.

However, I started getting this uncomfortable feeling that the wagon was pulling the horse, and I wanted the horse to be pulling the wagon. The evening length colorist performance All Blues at Baryshnikov Arts Center in June 2015 was a turning point. I choreographed and directed this piece, with a cast of eight. I realized through this project that my art and choreography was the trunk and the core of the studio and my practice. After this project, I flipped the ratio and focused on my art and choreography practice first and foremost, with the perfume editions being an extension of this core. I still produce the scents and other artist editions that people can purchase, and being able to share my work this way is important to me. I think of it as ‘publishing’ in a way. I enjoy this current work balance (75% art production 25% editions) - it feels more authentic to me.

Having a studio at times feels like being in a marriage. I know how much work and time has gone into it, so even if some days or months are hard, I know I am in it for the long haul. Like all good relationships, evolution is key. I wear a ring on my right finger that is inscribed with Atelier de Geste, and I think this keeps my thinking long-term and large-scale.

One of the aspects of ADG that I am so proud of is that I have worked with some amazing collaborators: Nouveau Classical Project, Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste, dancers Ella Misko, Chantal Chadwick, Kay Ottinger, musicians Lathan Hardy and Sugar Vendil. I really believe that we are nothing without our conversations and in relation each other. I try to prioritize this philosophical tenet; I see part of my work as a social practice – working in collaboration with other bodies, musicians, curators, artists – and I look forward to the expansion of this universe.

The other equally important part of my work is deeply internal – thinking, reading, moving, drawing – and I look forward to creating more time and space for this, through a new studio space, more travel and residencies. Also, more space for deep, unharried work and living.

Teaching is a great sharpening of my intellectual and creative sword, and a privilege to be able to give. I hope to continue to enmesh this work as part of my practice.

Sustainability is at the core of all the work you do, from developing scents, designing costumes, producing artwork, and you also teach a course Sustainable Systems at the Parsons School of Design. How did sustainability become such an inherent element of your work?

Instead of "sustainable", I like to think of this realm as biological & cosmological. They are less generalized and less confusing.

I have always been a tree-hugger-nature-lover, but I believe my dance background is my main entry into what I call a “bio-centric” point of view. Understanding my body as a dancer: in terms of mechanics, physics, force and weight, injury and weakness, is ultimately humbling. Dance is two-fold for me: on one hand it strips away any subjective specialness and strips you down to your anatomy. On the other hand, through this connection to anatomy (your living matter) there is also a spiritual connection to the self. Maybe by connecting with your physical constraints all the time, you realize that you are just an mammal in this much larger ecosystem. This is my starting point to “sustainability” – or what I like to call a bio-centric point of view. I like to think of it as a state of mindfulness, to be sentient and in touch with the living cosmos.

I have focused on having this ethos be central to my artistic practice as early as 2010; every creative choice is intentional; nothing is neutral. My priorities are: choosing materials intentionally, supporting smart labor practices through my work, creating ways to speak about the earth and cosmos through my practice.

However, in the last few years the urgency of environmental issues has become so obvious to me, and I wanted to roll up my sleeves in a more activist way. My part-time job as a communications & marketing director for an architectural design company Caples Jefferson Architects introduced me to LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). It’s an assessment system (not without imperfections of course) that determines how sustainable a building or space is. I decided to study this and get certified in 2016, as it seemed like a good way to have a conceptual toolkit to understand sustainability in a more specialized way.

One thing led to another, and teaching Sustainable Systems at Parsons this semester has shown me how much need we have in this new field. It is dynamic and overflowing with information, with both dystopic facts and hopelessness, but also tremendous room for innovation and evolution, and innovate we must!

I have discovered that people want to learn about sustainability in a level, supportive, and solutions-oriented way. The news and media do not provide this, at all; the approach is usually mind-numbing crisis alerts. So right now, I see my activism as my work in education through this course, my own small day-to-day mundane actions (like bringing my weeks’ worth of plastic bags to Fairway), and in a different way (more conceptual, communicative, aesthetic, emotional) through my art.

How can we integrate the ethos of sustainability into our daily lives and consciousness?

Practice mindfulness in your consumption of material goods: food, packaging, material possessions, clothing. Nature doesn’t waste things (falling leaves in autumn actually enrich the soil, every material is utilized) – so try to be like her. Bike more, walk more, carpool some, Uber less. Take trains if you can over airplanes. Commit to drinking coffee every day out of a beautiful thermos. Sign up to power your NYC apartment with green energy (you can easily do this- through ConEd or an ESCO like Green Mountain Energy). Commit to having a “steady state” of material possessions – if you buy a new thing, recycle/donate/upcycle something existing so you become super aware of if you are buying out of need or want. Immerse yourself in the wonder of nature.

What is your creative process? What does it mean to you to exhibit and create work?

There is no simple answer to this question, but I will attempt simplicity because one of my favorite quotes about creativity from Charlie Mingus goes: “Anyone can make the simple complicated. Creativity is making the complicated simple.”

My creative process, more or less, is my life sustenance and is how I live and navigate this world. I have a need for it that persists no matter what. My favorite tool, my body, I need to move it. I draw and note observations all the time. It’s a fire in my belly that doesn’t let me go. With my practice, I am able to process the messy muck of life and somehow make my life my own. Maybe it’s about finding freedom, simplicity, the strength to make a space of my own, the ability to have a point of view, and share this with others.

To be honest, it took me a lot of time to accept being an artist. Despite my inner spirit, and moving across the Atlantic for my MFA in 2010 in Switzerland without knowing a soul in the country, and all the sacrifices and choices made from college onwards to always put my artistic practice first, I shied away from the artist title for a while. It seemed to come with so much baggage, pomp and circumstance but at a certain point, maybe in 2015, I was just like, You know what? This is just who I am. Accepted. Committed. That was a huge liberation from certain limitations.

To give life to my work outside of itself, to propel its activities outside of its internal life, is an exhausting act of birthing (and fighting the monsters of self doubt). But, it is precisely this act of amplification, of stepping into a public arena, where you start developing dialogue, context, which is exciting. The work starts to be able to SPEAK in public. Once the work takes on this outside life, my art has already shaped the world in a different way. Like jazz artists improvising with each other, my practice has a place and it is speaking within and around and through voices and artists past and present.

Lately I have been thinking a lot about the amplification of work, process and practice; as an artist you are sort of like an athlete within an arena. A public figure, certainly. An exhibition, or exposition in French, is literally that: to be exposed, vulnerable, on view, open to critique, as much as you are open to connection.

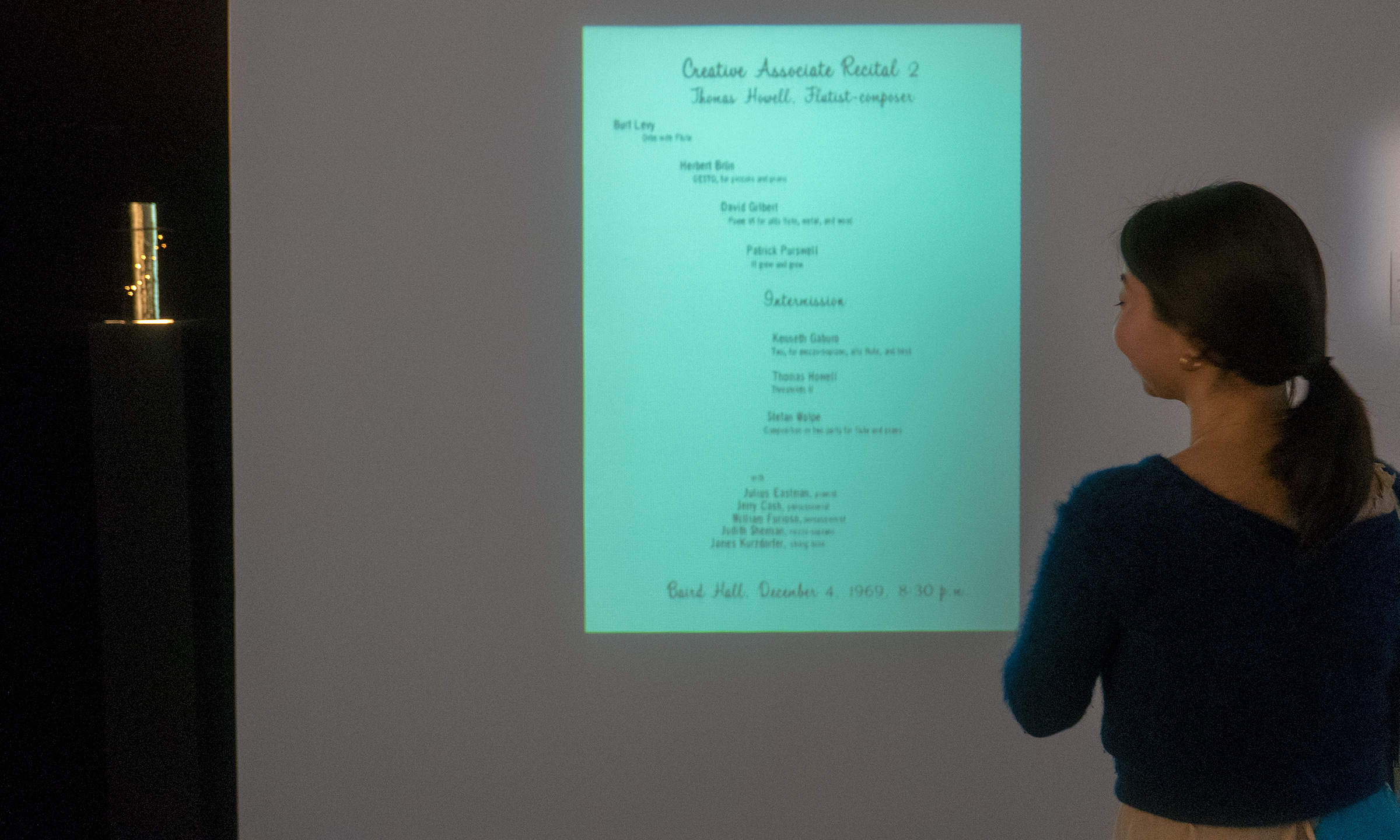

2017 and 2018 have so far been filled with very meaningful projects, like the exhibition I was a part of called That Which is Fundamental: Predicated honoring the life and work of Julius Eastman at The Kitchen, Naviguer à vue at Bard Graduate Center. I want my time and energy to be of service to concepts and works that speak deeply to people, that ask difficult questions in beautiful ways, that spark magical conversations.

I am proud of the work I did at the Bard Graduate Center gallery last summer – my "Corporality" drawing was a breakthrough and working with Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste and his sounds was really inspiring. Being a part of the exhibition at The Kitchen was a reminder of how powerful art can be: the show demonstrated how hard people like Julius Eastman had to fight to make art, and also the power of the collective – having fourteen of us young contemporary artists in his homage created a village, an amplifier around his work.

Has there been a defining obstacle in the course of your career thus far?

I would say that I have been the “other” in the majority of the contexts in my life, in both the West and the East. Racism in Boston and Europe was pretty overt; ranging from small day-to-day micro-aggressions to being called Chink or China pretty frequently. I think it’s insane that people ask you where your parents are from, and I say South Korea, and people say Ni-hao or Konnichiwa. Would you say Gutentag to an Italian person? There’s an ignorance to East Asian history and we all get grouped in together. My grandmother almost got killed by the Japanese during the Occupation.

Not to mention the baggage that comes with being an Asian woman in a white man’s world. Just sit with that sentence for a second. I think you can imagine what that means; expectations of gentleness and subordination, exoticism, being asked repeatedly, “No, where are you really from” and so on and so forth.

I will say, however, that New York City is the most race-friendly place I have lived, though, and it’s one of the main reasons it feels like home, actually. In Seoul Korea I am perceived as “slightly other” as well because it is so heterogeneous there that I seem foreign, which is strange. When I was a kid some of my peers asked if I was half-caucasian. I do love Seoul, despite its homogeneousness, for its food, the depth of culture and the emotiveness of Koreans.

Looking back, I also can’t believe how many white, male, Euro-centric artists I learned about as a Dance & Art History major at Columbia. Of course we had our Martha Graham moments in Dance and Dorothea Lange moments in Art History; but I think the ratio of female to male artists in the books was probably 1 in 20 (if that). Artists of color were discussed more in the Dance context, but in Art History near-to-zilch. I was so brainwashed that I didn’t even realize how skewed it was until I graduated school. Thankfully in Geneva my professors introduced more women artists into the mix, and I started deliberately searching for more references including women and artists of color in my lessons. Representation matters! I am very grateful to have been able to learn from Bill T Jones, Janet Wong, and other artists of color who paved the way.

How do you connect dance and performance to your roles as an artist/designer and perfumer?

The relationship I have with my body, my knowledge / understanding of body-space is my thruway to everything else. Everything I create – drawing, sculpture, costume, scent – is an extension of this choreographic point of view.

What have been some of the highlights of your career so far?

The most intimate, personal encounters. Mentors who become colleagues and collaborators. Peers who introduce themselves to me saying my work has touched them in some way. Conversations with my students where I am able to elevate their work and focus their direction. Knowing that my work (both creative and in education) is of service to others.

I quickly realized the glitz (press, awards, ceremonies) is the froth on the champagne. It is fun and important to have those public moments; however, the real value is person-to-person.

Who are some women that have inspired you?

More and more, the women in my family. My mother: pinnacle of strength, Virgo-meticulous-perfectionism, tough love, and she (in more recent years) has turned into one of the funniest people I know. My glamorous grandmother a self-made woman who endured everything (including the Japanese occupation) and made it look so effortless. I wish I had more time with her before she passed away.

What is your favorite time of day?

Dusk, when the sky turns smokey and the hustle bustle of the day cools off. I feel the time is ripe for dreams.

If you could listen to one song for the rest of your life, what would it be?

That is hard – can I make a medley? Probably the sound of the Atlantic Ocean at night in August on Fire Island. Or the Goldberg Variations by Bach. Charlie Mingus’ Mingus Blues. Frank Sinatra Street of Dreams (live at the Sands). Nina Simone Mood Indigo.

What scent could you never do without?

The smell of ocean on rock.