Aanchal Malhotra on collecting material memories and the potential of conversation as a tool for healing

Aanchal Malhotra is a writer and historian reorienting the way we think and talk about our past, present and future. Inspired by objects her family had carried with them during the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan, Aanchal began her journey of collecting and archiving objects, or material memories, treasured and preserved by displaced survivors of Partition, eventually compiled into her debut book, Remnants of a Separation.

Writing from New Delhi, India, Aanchal shared with us her words on the challenges and process of writing a book, and how conversations about our histories and generational trauma can foster tolerance in this age of digital overload.

Aanchal, tell us a bit about yourself.

I was born and raised in India and come from a family of booksellers. At the age of 17, I left Delhi and did most of my post-secondary education (BFA & MFA) in Canada. By education, I am an artist, a printmaker to be specific, having worked mostly in traditional engraving, lithography and typesetting and have now, with my recent work, become a writer and historian.

Remnants of a Separation, your MFA thesis, is the first and only material study of the Partition of India. How did this project unfold?

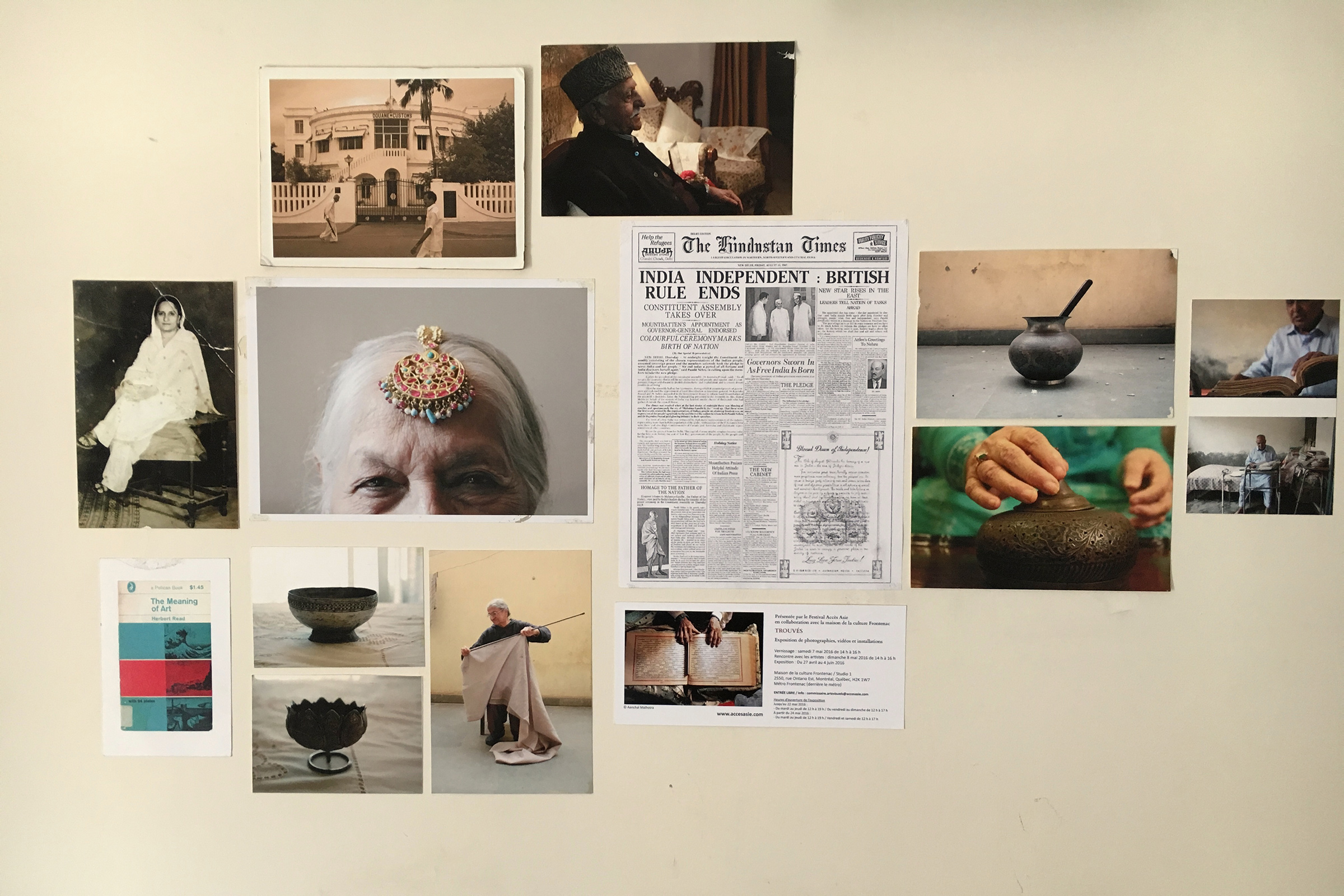

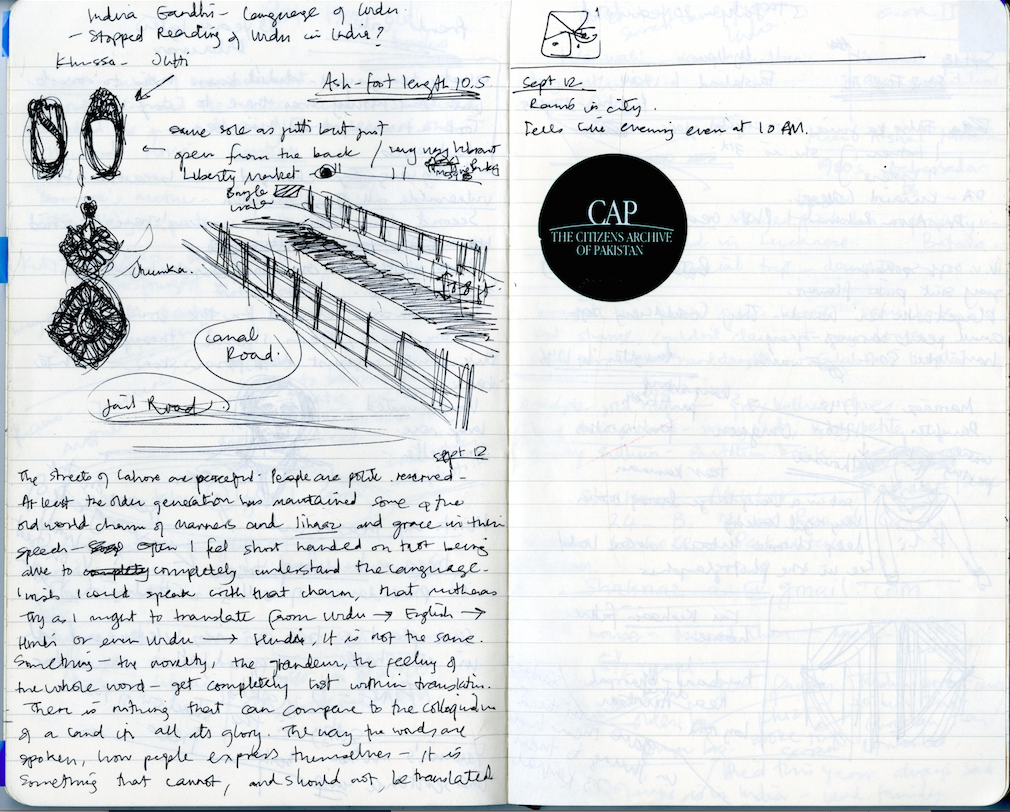

Well, my interest in the Partition began five years ago, and despite the fact that all four of my grandparents had travelled across the border to Delhi from various towns in what became Pakistan, I had never looked at the Great Divide with anything more than a cursory glance. But it was in 2013 that I was introduced to two objects that my maternal grandfather’s family had carried from Lahore, mundane objects, a vessel in which milk was churned by my great-grandmother, and a yardstick, used by my great-grandfather in his clothing store. And when these two objects were brought out, caressed and talked about, they seemed to inspire memories of a landscape long rendered inaccessible by a national border. And the longer we spoke about these two objects, the more ‘real’ Lahore began to appear to me. This began an exercise in the excavation of the past that took me across India, Pakistan and England. It began with my family, of course, but soon I started speaking to strangers and people from all communities, trying to use migratory objects that had crossed during the Partition as catalysts for remembrance, and treat them as storehouses of memory, especially if that memory was one of trauma.

“Remnants” has since then evolved into your debut book; what was the motivation for recreating your thesis in this format?

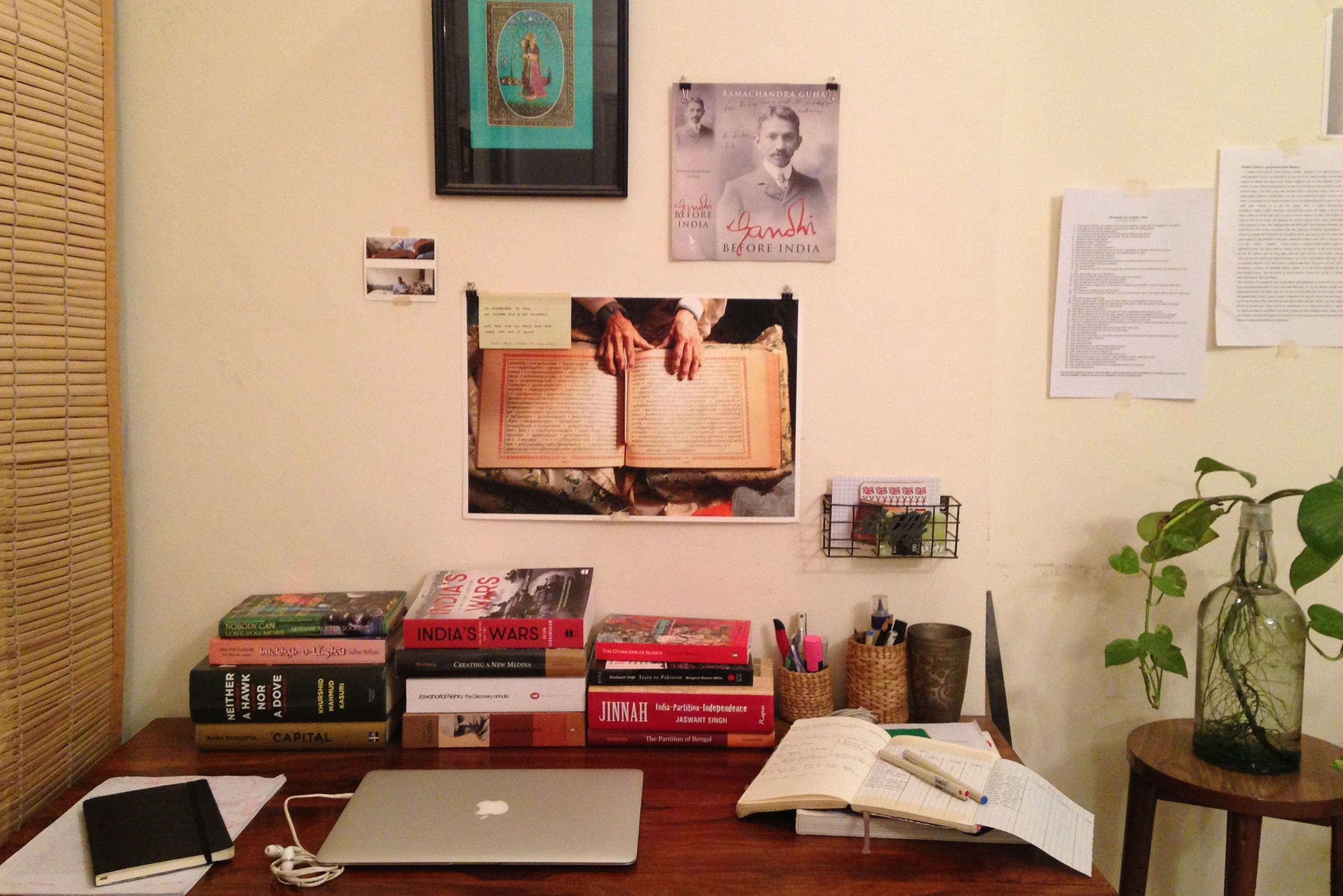

When I began these interviews, it was never with the intention of writing a book. It was first to quench curiosity, then to document visual material (photographs of the objects) for a fine arts thesis and gradually, it started taking the form of the written word. But even before it became a book, I had started documenting snippets of the stories in a blog I called ‘The Hiatus Project’. Since ‘Remnants…’ began as a hiatus while on sabbatical from my MFA life in Montreal, I saw this to be a fitting title for the blog. And I started putting these blurbs out there on the internet, for a few reasons...one of course, because they were heavy and dense in content, and in turn made me heavy. There was a sense of responsibility that came with listening to first-hand accounts of the Partition and I wanted to do justice to them. But the more important reason, and this is also the reason for writing the book, is that I was listening to things that other people of my generation needed to hear. We, who had only read about the Great Divide in our history textbooks in school needed to hear stories from both sides of the border- stories about courage and sacrifice and even violence and bloodshed, but first-hand stories.

What went into the process of documenting this material memory?

It would usually start off as a simple conversation, never beginning with Partition but usually with mundane topics like weather or politics, or what one did during the day. And then the exercise in excavation of memory would begin, usually through the object. Shawls, books, curios, photographs and oddities from a time gone by would be brought out and discussed at great length, and through them, we would venture into landscape and geography of a home across a man-made border. And eventually, we would get to the word Partition or batwara or taksim, and only when we had established trust or a certain level of comfort, would that word be unpacked and talked about. My questions almost always grew from the answers I would get and so the structure of the interview was less formal and more conversational. I would photograph the object, understand what it means to the person and sometimes even to their subsequent generations, but most of all, in these interview sessions, I would listen.

What is one story from “Remnants” that you will never forget?

The story that has no object! Chapter 10 of my book is about a man named Nazmuddin Khan, who is from Delhi and remained in Delhi during the Partition. His father was a part of the security as Viceroy House and when the Divide was announced, he was asked, as a Muslim, to travel to Pakistan and join Mohammad Ali Jinnah's security in the new state. I had gone to see Mr. Khan because I thought he would show me something from Viceroy House- a badge or a newspaper clipping or a photograph or an ID card. But when I arrived, he had nothing. He had no object to show me, no physical ‘thing’ to connect him to that time. Nothing. And the silence that accompanied this nothing really frightened me. He was sorrowful, the sadness enveloped him and what he taught me that day, was far greater than any object whose story I could have archived.

These are some excerpts from his chapter in my book, titled 'The Hopeful Heart of Nazmuddin Khan':

‘My father used to say to us – Hindustan is our vatan, our land. It didn’t matter that we are Musalmaan; what mattered was that we were born here and here is where we would die. We didn’t belong anywhere else except on this soil. And ever since we were very young, he made sure that we knew the importance of being loyal to the land.’

This he said with conviction, both palms flat and erect, pointing deep into the ground to emphasize the reality of his physical belonging. Each word embodied the values his father had instilled in him. And it was not that he was attempting to divulge a fact of great significance or philosophy. In fact, whatever he told me that afternoon was so candid and uncomplicated that to my jaded ears it sounded impossibly mundane. He described what, in my opinion, was the purest way to understand the essence of secularism in regards to India.

‘Our Hindu brothers,’ he began, ‘are born in Hindustan, they grow up here, live their lives here, they die here. And when they die, they are cremated and their ashes are immersed into holy waters of the river Ganga. Within her tides they flow, even if it is eventually into foreign waters. But look at us Musalmaans...we are born in Hindustan, we grow up here, we live here and we die here. And when we die, we are buried deep into the ground and, eventually, when our bodies decompose, we become one with the land. We become Hindustan.’

Then slowly, still seated on the sofa, he bent his stiff, wiry frame halfway to the ground and patted the floor with his palm. Straightening himself back up, he heaved a loud sigh. ‘We become Hindustan. Iski mitti mein mil jaate hain, our bodies mix into its soil. How could we ever leave this land, then? Our home, our life – how could we ever leave it? We are within the very land.

I had gone there to look for things, but what he gave me was something so much larger, much bigger than I could hold or take care. A simple notion of secularism. And often these interviews would take these turns, where I would be given responsibility, as it were, of people’s pasts and how they felt and there was a need to write these down. Zaroorat, the Urdu word for zaroorat is need. I needed to archive these kinds of memories.

Was it challenging to document and retell the memories from a deeply tumultuous time – both socially and politically – for the the South Asian diaspora?

Yes, I think so. Partition is a subject that has been spoken about for the most part, in hushed tones in private chambers, and never has there been a public discourse about it. It was never something one spoke about and for people who witnessed it, perhaps they didn’t know how to begin talking about it. What words does one use, how can one memorialize a place that is likely never to be seen or felt again?

Only now, in the recent decade, has there been a surge of work and information about archiving first hand memories of the Partition. Yet, remembering it continues to be arduous and difficult and memory – as age goes by – becomes unreliable and malleable and is no longer chronological. What we must strive to do is tell the story of this time as a marriage between academic and oral history. Neither one encompasses the sheer depth and magnanimity of the event by itself. It is only in conjunction with fact and memory that we can truly weave a cohesive tapestry of the happenings around Partition and the Independence Movement of 1947.

It is also challenging, because in doing these interviews, I am crossing many many borders. Not just geographic ones, but also those of age. I am speaking to people many decades older than me, and I am aware of the pain my questions are causing them at times, but I am also aware that this is the only way we – my generation- will ever know. This is the only way we will archive memory. Often, these conversations are emotional and draining and I find myself suddenly on the end where I am meant to comfort an aged person, whereas it would have otherwise been the other way round. The roles get reversed often and that is a difficult situation to be in. To tread on fine lines, to pull on impossible strings, to constantly evoke the past.

Your family owns New Delhi’s esteemed bookstore, Bahrisons, which was established in a post-Partition climate. How has your family history and literature influenced your work as a multidisciplinary creative?

Well, I’ve grown up around books, they have been a constant in my life, which meant that because I read so much, I travelled the world through the written word. I think being aware of the history present in even my family’s work – the bookshop was begun by my grandfather Balraj Bahri, in 1953 after he came from Malakwal into Delhi as a refugee during the Partition – had made me feel such enormous respect for not just the written word but also the efforts of refugees that came with nothing. I am lucky that my family supported my decision to travel across the world to study art and I am thankful for that everyday. But I think what really defines my practice is the access to the written word. It is in my blood, there is no denying it, whether as a reader, a writer or a bookseller, I breathe words. Despite having been trained as an artist and to think in images, words remain the best way I know to express myself.